First published on the London Historians’ Blog May 2016. Many thanks to Mike Paterson for making this possible.

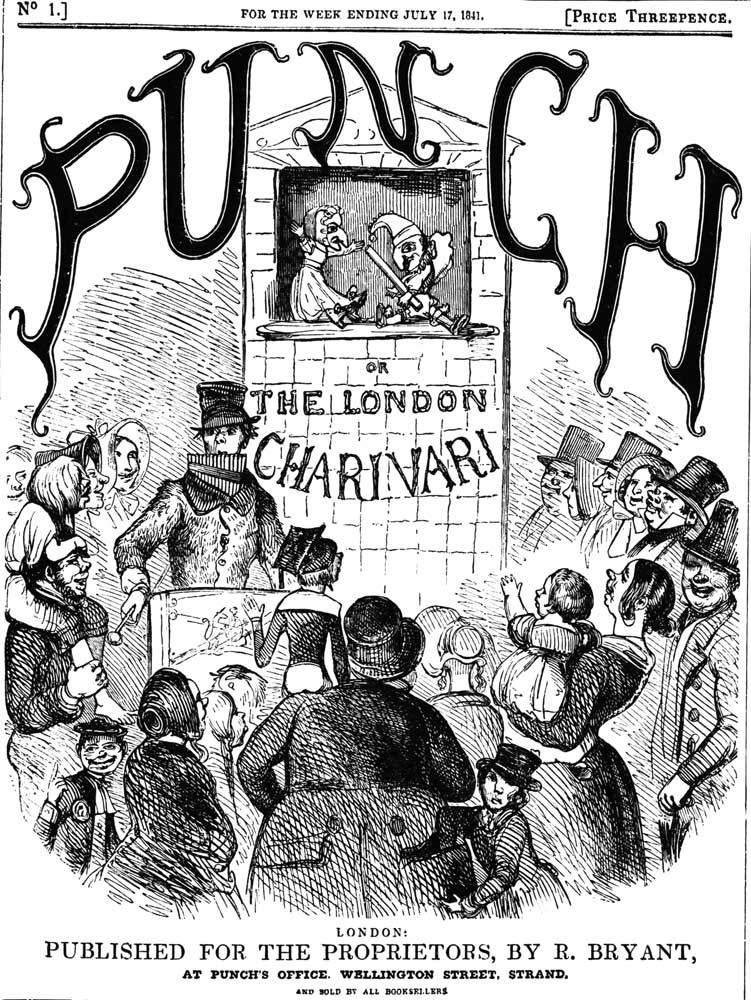

175 years ago, ten years before London Labour and the London Poor, on Saturday 17th July 1841, Henry Mayhew hovered about the offices of the publisher, Mr Bryant, at 3 Wellington Street, the Strand. Nervously he listened for news of the first issue of Punch. He had spent a sleepless night with his co-owners at the printers, watching their new paper emerge. As day broke they

… walked up and down outside the office, and in the neighbouring Strand, discussing the paper and its prospects and constantly calling to hear from Bryant how things were progressing. At news of each fresh thousand sold, their spirits rose, and their anxiety became satisfaction when the whole edition of five thousand had been taken up by the trade, and another like edition was called for, and, on the following day, was sold out. Ten thousand copies! Ten thousand proofs, they took it, of sympathy and encouragement. [i]

Punch became one of the most successful magazines of all time, a pillar of Victorian culture and beyond, finally closing in 2002. Yet Mayhew’s role in creating it and ensuring its survival in its precarious early years was largely forgotten long before then.

on sale as Mayhew paced the Strand

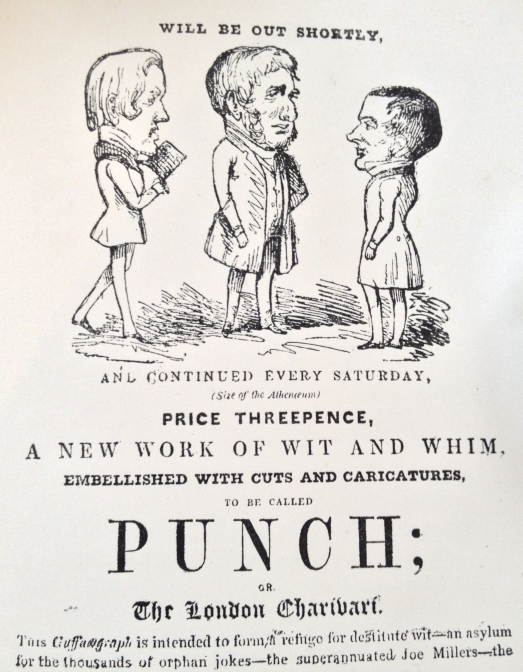

Punch, or the London Charivari was the direct descendent of Figaro in London, both localisations of Parisian satirical papers with a radical edge. Set up in 1834 by Mayhew, his elder brother Thomas and their old Westminster school friend, Gilbert à Beckett, Figaro mixed cartoons, humour and investigative journalism, in a winning formula that saw circulation reach 70,000 at its height. Mayhew’s was the junior role, writing light sketches and puns under the pen name of ‘Ralph Rigmarole’, and intermittently editing the paper too. Figaro closed in 1839, but its ethos and personnel found a new home in Punch.

At the start Punch was pure London Bohemian, an edgy mixture of radicalism and wit, drawn from the circles that had contributed to Figaro and drunk away days and nights together at two favoured pubs, first The Wrekin in Convent Garden, followed by The Shakespeares Head in Wych Street, a notorious medieval survivor, where the ‘tobacco shops’ were fronts for brothels and the print shops specialised in pornography. The landlord of The Shakespeares Head, Mark Lemon, was an aspirant dramatist and close friend of Mayhew’s. Together with two refugees from Figaro, the printer Joseph Last and the journalist Stirling Coyne, and the engraver Landells (who put up most of the money), they came up with the idea of Punch. Mayhew was the creative force, organising the content, recruiting contributors and negotiating terms.[ii] Apart from Lemon, Coyne and himself, his all-star crew of London wags included à Beckett, Douglas Jerrold, Harry Baylis, H.P. ‘Harry’ Grattan, and George Hodder, soon joined by William Thackeray, who Mayhew had got to know in Paris in the mid-1830s when sheltering there from the London bailiffs.

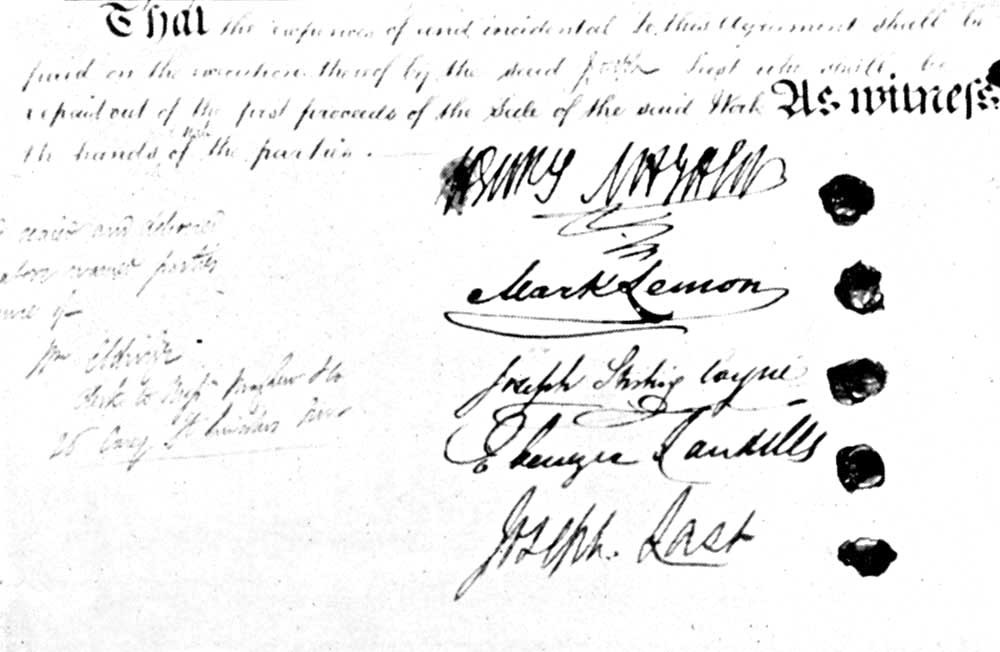

Mayhew also arranged the formalities, setting up Punch on a ‘cooperative principle’. He had his brother Alfred, a lawyer, draw up the Punch Articles of Agreement. The five founders signed these at his father’s law office at 26 Carey Street on 14th July 1841. The Articles appointed Mayhew, Lemon and Coyne as co-editors, Landells as the engraver and Last as the printer. The five had equal shares in the ownership and, hopefully, the profits. Roles and responsibilities were defined, as was the format of Punch, adopting the Figaro formula:

That there shall be published a periodical Work to consist of humorous and political Articles and embellished with Cuts and Caricatures to be called ‘Punch, or the LONDON CHARIVARI’ the same to be published in weekly numbers every Saturday…

The coterie at the heart of Punch dubbed themselves The Punch Club and ran it as a creative collective, Mayhew, Coyne and Lemon the first among equals. Raucous editorial meetings, with Baylis in the chair, convened in The Crown, Vinegar Yard, where the copy, sketches and ideas for each issue took shape in smoke-filled boozy evenings, over a dinner of beef or mutton and apple pudding, the meetings open to all but dominated by the veterans of The Shakespeares Head and The Wrekin. [iii] Ominously, after initial success, sales began to trail off. Sages predicted a quick demise. Mayhew recalled:

The customary group of croakers surrounded the place in which the little hunchback first saw the light. They gave him a short thrift – considered his conception good, but his delivery premature – and took their sapient affidavits that his circulation would never be sufficient to keep him going from week to week. [iv]

By the autumn it looked as if the “croakers” might be right. In October, in return for a loan of £150, the founders contracted the printing to Bradbury and Evans. William Bradbury and Frederick Evans owned the most advanced printing works of the day at their premises in Whitefriars, Fleet Street. A reputable, well established firm, their credits including Pickwick Papers, they were wary about the risk to their reputation associating with Punch, given its provenance. The losses persisted. The new investors, Mayhew and the remaining co-owners (Last and Coyne had departed), huddled in pubs on the Strand, discussing whether to cut and run.[v] To cover expenses, Lemon knocked out farces for the Strand Theatre, including Punch on the Platform.[vi] A talking parrot featured in the cast. One night, Lemon recalled, the regular parrot fell ill, and the stand-in parrot “…instead of saying what it ought began ‘show us your cock’.“[vii] Despite this, the farces failed to pay. Despite weekly sales of several thousands, Punch ended its first year £600 down.

It fell to Mayhew to save Punch. He decided to bring out a festive spin-off, the Punch Comic Almanack. The plan was to co-write it with Harry Grattan, but there was one snag. Grattan was locked up in the Fleet prison for debt. Undaunted, Mayhew bribed the guards to let him stay a week there too until they finished the Almanack. As Grattan recalled:

…It was against the rule for any person, not having a legal right, to sleep in Her Majesty’s establishment; but, and not for the first time, the rights of the Crown were superseded by half-crowns properly and judiciously administered to the turnkey on duty, and for seven days and nights Mayhew was a voluntary prisoner… [viii]

Punch’s Comic Almanack sold over 150,000 copies and saw Punch safely through to 1842.

Lacklustre sales and the continuing lack of funds led to a full buy-out by Bradbury and Evans by December 1842. Reflecting on the life of Punch up to this point, Mayhew said:

To me Punch was always a labour of love, and certainly never proved a source of profit; for, after panning and arranging the entire work, selecting the whole of the old staff of contributors, and having edited it for the first six months of its career without having received a single farthing for my pains, it so happened when those who started it were obliged to sell their bantling to Bradbury and Evans, that on the payment of all the debts connected with the production of the work, there remained a clear surplus of seven and sixpence to be divided among the three original proprietors, of which the munificent sum of half-a-crown fell to my share. [ix]

Under the new regime, Punch began the gradual transition from “the journal of Bohemia” to “the mouthpiece of Mayfair”.[x] Shrewdly, Bradbury and Evans continued to nurture the core talent but rationalised the management. Lemon became the sole editor. Mayhew became ‘Suggestor-in-Chief’ a creative role well suited to his temperament, on a salary of £200 a year. This change has often been portrayed as acrimonious, and the reason Mayhew left Punch, but this is a myth. He remained happily engaged on the paper he founded for another four years in his new capacity. [xi] It was only later that the memory of these times soured, when a “confrontation” led to Mayhew being sacked, then trying to claim money for dismissal off of his erstwhile colleagues in the Bankruptcy Courts. [xii] But that is another story. Lemon remained as Punch editor until his death, in 1870. After his departure, Mayhew was shunned, yet in the privacy of the Punch dinners, Lemon never failed to give him credit for his part in the birth of the cultural force that was Punch. [xiii]

Sources

[i] M.H.Spielmann, The History of Punch, p.33, 1895

[ii] The Pierpont Morgan Library, New York. MA4500

[iii] Athol Mayhew, A Jorum of Punch, p.93, 1895

[iv] Athol Mayhew, A Jorum of Punch, p89, 1895

[v] Henry Silver Diary 1858-1870, entry 11th July 1868, BL MS 88937/2/13

[vi] Henry Silver Diary 1858-1870, entry 7th March 1866, BL MS 88937/2/13

[vii] Henry Silver Diary 1858-1870, entry 9th December 1858, BL MS 88937/2/13

[viii] Athol Mayhew, A Jorum of Punch, p83-87, 1895

[ix] Athol Mayhew, A Jorum of Punch, p121, 1895

[x] Arthur William à Beckett, The à Becketts of Punch, p86, 1903

[xi] Letter from Mayhew to Paxton, December 14th 1858, Devonshire MSS, Chatsworth

[xii] Horace Mayhew to Evans, Bodlean Library, Punch Archive, 2279-6

[xiii] Henry Silver Diary 1858-1870, entry 8th January 1862, BL MS 88937/2/13