First published on the London Historians’ Blog November 2015. Many thanks to Mike Paterson for making this possible.

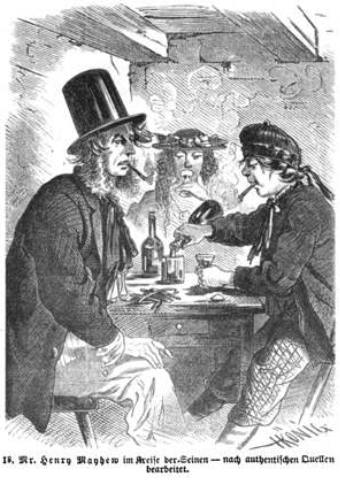

In July 1870 France and Germany went to war. The conflict would decide continental supremacy, and it nearly saw Henry Mayhew shot as a spy. English journalists flocked across the channel. The Globe and Traveller, a London evening paper, appointed Henry Mayhew as their correspondent. Mayhew was not such a surprising choice. Since London Labour had folded in legal disputes in the early 1850s, Mayhew had spent time living on the continent, mainly in Germany, in Cologne and in Eisenach, Saxony, driven by the need to escape debtors back in London. Abroad, he could live cheaply and study the local culture. He wrote two travel books on the Rhine in the 1850s, and a massive anthropological study, German Life and Manners, in the 1860s. His view on the Germans as a people was so scathing that the Leipzig Illustrate Zeitung hit back with a double paged spread of cartoons lampooning the English in general and Mayhew in particular. In England, his views won him friends. The Daily Telegraph appointed him to cover the Schleswig-Holstein crisis in 1864, Denmark’s futile opposition to the rise of German power. Imperial France was another matter. As Mayhew headed out to cover the new war, he anticipated a walkover. Of German aspirations to national greatness he had written: “As well might a community of squirrels hope to rank among the higher powers of Europe.”[1]

Mayhew’s reports for the Globe were anonymous, written under the by-line ‘Our Special War Correspondent’. Arriving in Strasbourg he noted the bombastic party atmosphere:

The privates are reeling six abreast along the streets roaring the “Marseillaise” and shouting “Aux Armes!” with all the stentorian pot-valiance of Strasbourg beer. [3]

His destination was Metz, the HQ of the French military close to the border. Here, with his son Athol in tow, he joined the band of ‘Special Correspondents’, English journalists which included the likes of George Augustus Sala for the Telegraph and O’Shea for The Times. The police watched them closely. Mayhew was informed that any ‘Special’ caught among the French lines would be immediately shot as a spy. He settled into the Hotel de L’Europe, enjoyed the fine dining and amused his readers by debating if he would prefer to be hung or shot. He decided it would depend on his mood.

Cooped up in Metz, drinking and bored, one by one the ‘Specials’ were picked up by the gendarmerie on suspicion of one sort or another. With nothing happening in the actual war, Mayhew sent up the phoney one:

Since writing you the war against the specials has been raging more fiercely than ever. Two of the envoys from the rival illustrated papers have been lately arrested. This, to say the least, shows that the military authorities are determined to carry out the principle of strict neutrality; for if the gentleman in connection with the Illustrated London News is to be hurried off to the police bureau for sketching in the streets, assuredly the one representing the Graphic ought to be taken up also: and it does infinite credit to the impartiality of the sergents-de-ville here to be able to add that such was really the case. [4]

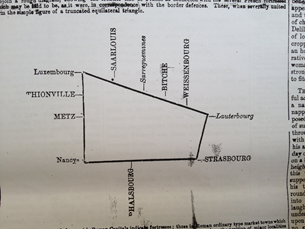

On Monday 1st August, Mayhew and Athol managed to escape Metz for the border town of Thionville. Wandering around the crowded market, they chatted in German, and were promptly picked up as Prussian spies. Returned under guard to Metz, his friend, Sala, secured their release. The English ‘Specials’ met to discuss how to deal with the increasingly aggressive surveillance, Mayhew complaining about how his movements were being were being spied on. When news came in from the front a French attach on Saarbrucken, their frustration grew.

Undaunted, the next morning, Mayhew gave the police the slip by heading to the station before dawn. Waiting for the first train, he spent a couple of hours drinking at the station buffet, mixing coffee and liqueurs: “I never drank so much, indeed, at such an early hour in my life. But what was one to do?” Reaching Forbach, Mayhew found that the reports of French triumphs across the border in Saarbrucken were just propaganda. He headed back to Metz to file his scoop with the Globe, and packed to return to Forbach first thing the next morning. In his absence, the Germans stormed into Forbach, slaughtering the French garrison.

When the news reached Metz it sparked panic and paranoia. Mayhew noticed how:

… a sorry change had come over the people since the disasters of the army on the frontier at Forbach. They no longer went swaggering and singing about “Mourir pour la Patrie.” The patriotic gas had blown off, and the insane suspicion of war’s alarms had set in…”The town,” cried the people, “is full of spies.”…The next morning the people who but a few days ago had made so certain of annihilating the Prussians, became positively insane with fright. The news spread that Metz was to be besieged, and that the town would be betrayed by spies to the enemy. “We have been generous,” said the citizens, “We should have turned all the strangers out long ago.

That Sunday morning, as wounded French troops began flooding in, Mayhew went to explore what was happening at the station along with a journalist for the Dally News and an artist from the Illustrated London News, Mr Simpson. The came across the Emperor Napoleon’s baggage being readied for a sly exit. Simpson began sketching the scene, openly to allay suspicion, but drawing hostile crowd. Denounced as spies, within minutes armed troops were marching them forcibly to the guardhouse in the Place d’Arme:

Then no sooner did we begin our march through the streets of the town than the people, seeing us in the custody of so large a body of the Garde Mobile, took us for the most desperate characters, and accordingly they one and all flocked after us, shouting “A bas les Prussians!” “Mort aux espions!” “A la lantern avec eux!” and so on; the crowd increasing every moment by the way, and the people rushing up to us frantically and shaking their fists or the handles of their umbrellas furiously in our face. “You! You old scoundrel,” said they to me (for I seemed the special object of their hatred) “are the worst of all. We’ve seen you about for the last fifteen days, and we’ll give you a coup de fusil now we’ve got you. [6]

The jail was besieged by “…two or three thousand people…howling for our immediate execution.” Locals queued up to testify to their guilt. The Commander of the City, General Coffinieres, arrived to interrogate the captives personally, quizzing Mayhew about the ability of him and his son to speak such good German. Mayhew was held for six hours and “…treated by the cowardly mob with insults which I had never experienced all my life before.” Eventually he was released but expelled from the country. He was given an armed escort back to his ransacked hotel room. The next day he was put on the first train out of Metz. From Paris, on Thursday 11th August, he filed his final report on the war for his London readers:

In as few words as possible, I had a narrow escape of ending my career a la lantern – of being torn to pieces by the frightened populace of Metz last Sunday; and was ordered to leave the town by the first train on Monday. And for what? Firstly, for being mistaken for a Prussian spy; and, secondly, for being proved to be the correspondent of an English newspaper. Voila tout! [7]

By the time it was printed in The Globe he was safe in London. Within a month Metz had and Paris was under siege. Mayhew’s comment about the community of squirrels was politely forgotten.

Sources

[1] German Life and Manners, Vol 2, 1864, p.608

[2] Illustrate Zeitung, Leipzig, 2nd July 1864

[3] The Globe, Saturday 23rd July, 1870

[4] The Globe, Wednesday 3rd August, 1870

[5] The Globe, Thursday 28th July 1870

[6] The Globe, Thursday 11th August 1870

[7] The Globe, Thursday 11th August, 1870