First published in September 2017 in the Wandsworth Historian , the journal of the Wandsworth Historical Society. Many thanks to Neil Robson for making this possible and applying his sharp editing skills.

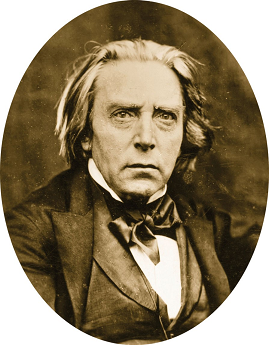

Born in Kent in 1803, Jerrold became a midshipman at the age of 10 on the HMS Namur. Captained by Jane Austen’s brother Francis, the Namur ferried the wounded home from Waterloo. His father, a theatre manager, moved the family to London in 1815, where Jerrold became a printer’s apprentice, in his spare time submitting articles and verses of his own, and working his way into journalism proper, an emerging trade in the Regency print boom. His first play, More Frightened Than Hurt, written when he was 14, was staged at Sadler’s Wells Theatre in 1821. His hope was to revive English drama at a time when theatres were awash with translated French farces. His one great success, Black-Eyed Susan, a romance framed by aristocratic corruption and the navy’s press gangs, came early in 1829. Thereafter his plays failed to have the impact he strived for, and he increasingly fell back on journalism to earn his living.

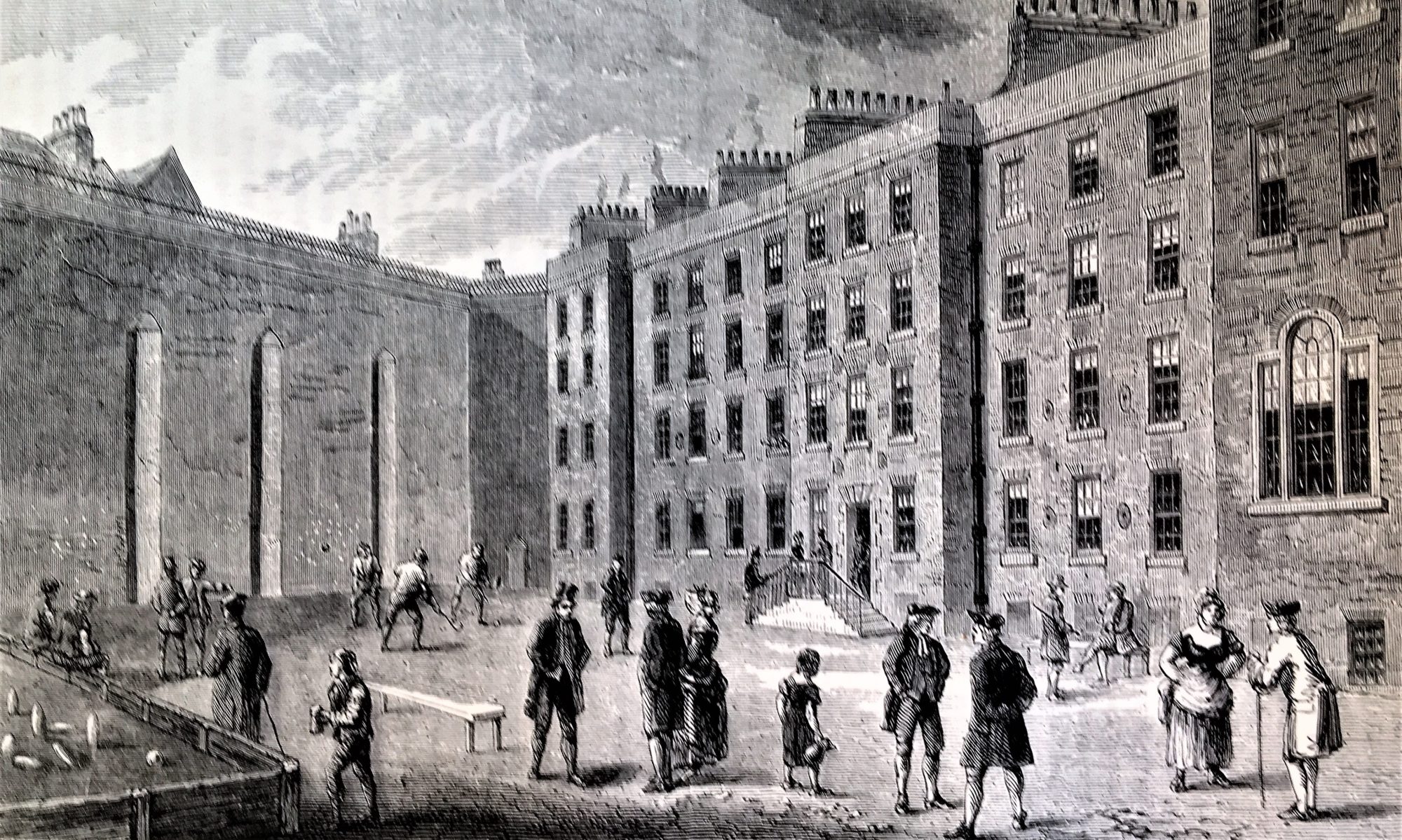

He was dogged by debt. A spell in the King’s Bench Prison in 1830 was followed by frequent flights abroad to evade the bailiffs. On one sojourn in Paris in 1835 he met Henry Mayhew and William Thackeray. The three passed happy evenings quaffing wine and dreaming up literary schemes.[i] Mayhew is best remembered today for his London Labour and the London Poor, a unique record of the voices of London street folk, which was serialised between 1850 and 1851. Blending interviews and observations it remains a time-capsule of the Victorian poor. It has endured as a pioneering work of sociology and Mayhew regularly features in the History National Curriculum in schools today. When Jerrold met him in Paris though, he too was an out-of-luck dramatist and comic journalist on the run from his creditors. Paris marked the beginning of a friendship that would bring Jerrold heartbreak.

Whereas Dickens and Thackeray wrote lengthy books that served as their legacy, Jerrold shone in magazines and newspapers, reflecting his time brightly but in an ephemeral form that would pass with the age. Among contemporaries, Jerrold’s status was based on his brilliance and wit as a conversationalist and raconteur. He was at his best in company, holding court in the inns and clubs of the West End where Victorian writers and dramatists congregated at all hours to swap ideas, drink, hatch new journals and schemes, ‘chaff’ each other, and then drink some more. The Evans’s Supper Club and The Rationals in Covent Garden were two of the more bohemian gatherings which Jerrold presided over. When Mayhew launched Punch in 1841, and at the same time the ‘Punch Club’, he recruited his writers from these very places. Jerrold was a natural choice, contributing from the second issue of the paper and continuing with Punch for the rest of his life.

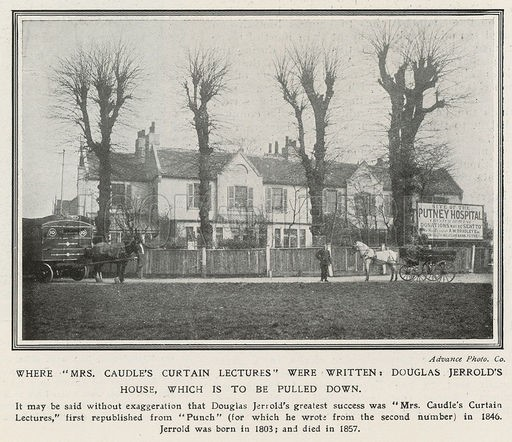

Yearning for his usual company, Jerrold urged all his friends to visit, joking he had moved ‘into the desert … [but] there is an oasis, in the shape of an excellent garden, out of which I hope to dig two or three plays and books of a better quality than any yet from the same hand’.[v] As a result the London literati were lured to Putney, Dickens, Thackeray, and the Punch editor Mark Lemon among them. Jerrold kept open house for all-comers on Sundays. They may have raised eyebrows among his largely local-born neighbours – carters and gardeners used to simpler, Putney ways. The railway would not come until 1846, so they arrived by steamer from the Strand or by coach across the wooden bridge, to dine and drink in a tent under the huge mulberry tree in Jerrold’s garden. Blanchard Jerrold described those afternoons like this:

Perhaps the fun may be extended to a game of some kind, on the lawn. Basting the Bear was, one evening, the rule, on which occasion grave editors and contributors ‘basted’ one another with knotted pocket-handkerchiefs, to their hearts’ content. The crowning effort of this memorable evening was a general attempt to go heels over head upon hay cocks in the orchard. [vi]

His garden was his joy. He grew strawberries ‘big and square as pin cushions’,[vii] asparagus, cabbages, geraniums, and he kept chickens and a cow, and cultivated an orchard. Here is how Blanchard painted his morning routine:

It is a bright morning, about eight o’clock, at West Lodge, Putney Lower Common. The windows at the side of the old house, buried in trees, afford glimpses of a broad common, tufted with purple heather and yellow gorse. Gypsies are encamped where the blue smoke curls amid the elms…. A little, spare figure, with a stoop, habited in a short shooting-jacket … and crowned with a straw hat, pushes through the gate of the cottage and goes, with short, quick steps assisted by a stout stick, over the common. A little black-and-tan terrier follows, and rolls over the grass at intervals, as a response to a cheery word from its master. The gypsy encampment is reached. The gypsies know their friend, and a chat and a laugh ensue. [viii]

[source: alchetron.com]

An outrider passed us in scarlet or crimson livery and then another. We stood and saw the Queen pass in a char-à-banc, containing twelve people. Prince Albert sat in the second row.… The impulse to raise my hat was strong, but as D. J. did not, I too refrained…. D. J. told me she had turned Punch out of the Palace. [x]

Jerrold kept up his old city ways too. A friend in town came across him legless after the weekly Punch editorial dinner. His colleagues eased him into a cab ‘with a label tied round his neck, on which was written: “Douglas Jerrold, Esq., Lower Heath, Putney”’.[xi] They assured him this was usual. Another recalled that Jerrold ‘was fond of the Garrick Club, or of any boozing place. There he remained till the small hours, when his brougham with half-sleepy coachman then drove him to Putney well soaked to bed’.[xii]

Mrs Caudle’s Curtain Lectures may owe something to the reception he received on his return to Putney Common. Written in West Lodge and serialised in Punch between 1845 and 1846, the thirty-seven ‘lectures’ were Mrs Caudle’s bedtime monologues delivered to her drowsy spouse. His rare, tentative defences are mercilessly parried by her withering replies. His common misdemeanour was returning late on the feeblest excuse, the worse for wear and smelling of tobacco smoke ‘enough to poison a woman’. Other charges included flirting with the servants, his ‘shameful indifference’ when French customs officials frisked Mrs Caudle on their way to Boulogne, and his ‘unmanly cruelty’ in refusing to smuggle goods past them on their way back. Moreover he was accused of spending too much time with his best friend, the louche, insolvent Mr Prettyman and his coquette of a wife, of joining the Freemasons, of speculating in railway shares and of not displaying sufficient enthusiasm at the idea of his mother-in-law coming to live with them.[xiii] Mrs Caudle’s Curtain Lectures became a national obsession and a bestseller when published in book form in 1846, remaining in print into the next century.

[source: www.digitalcommonwealth.org]

Their first child, Mary, arrived in 1845, and Jane was pregnant with their second by 1846, by which time Mayhew’s debts approached £2000 (£220,000 in today’s terms).[xvi] His behaviour deteriorated under the stress, and what Jerrold described as ‘his insane conduct’ began to alienate his Punch colleagues, losing respect and friendships. Jerrold was most alarmed at the position in which the worsening situation left his daughter and grandchildren. In a letter to Mark Lemon following one distressing evening, he made his feelings clear:

Again, three weeks ago I mentioned the subject to Mayhew, and I think with you it may be the same. I cannot express to you the mingled pity and disgust excited in me on Saturday. There is only one consideration – that of my girl – that makes me neutral as to acting …for I would rather think it madness than badness. Perhaps there is a little of each. [xvii]

He was sacked soon after, with the backing of Jerrold and Lemon, following a ‘confrontation’.[xviii] Bailiffs circled The Shrubbery in Parsons Green, where the heavily pregnant Jane was left to fend them off alone. Worse followed. The ‘Railway Mania’ bubble burst, sinking the Iron Times with it. On 11 June 1846 Jane gave birth to Athol. The day she registered the birth Mayhew had himself declared insolvent, and was officially listed as bankrupt in the London Gazette on 27th July. Jerrold wrote in despair to Dickens that October:

My dear Dickens, I have been much worried … by one of those grave evils of life which I hope you may be spared. I have found that to marry a daughter is to bury her…. In his wild, unscrupulous way, he ‘at least behaves well to her’, people say; that is, he does not beat her – although, in the most reckless manner, he sacrificed her home, and brought bailiffs prowling about her child-bed. [xix]

When the bankruptcy court ruled that Mayhew had been profligate and refused him protection from his creditors, he fled beyond their reach with his family to Guernsey. To restore his fortunes he began, with his younger brother Augustus, to write comic serials under the name of ‘The Brothers Mayhew’. First came The Greatest Plague of Life, about a woman hiring one disastrous servant after another, and then there followed Whom to Marry and How to Get Married!, about a woman getting engaged to one unsuitable man after another. Both were great successes, and written from a woman’s perspective, indicating Jane was one of ‘The Brothers Mayhew’ bringing her father’s gift with words. Twenty years later Mayhew publicly acknowledged her as the ‘sleeping member’ of the firm in this tribute:

Those who know how much of the genius of your father you have inherited will readily believe that you brought no little wit into the business as capital (and let me add, parenthetically, capital! it was). [xx]

During their Guernsey exile, Jane fell seriously ill. Jerrold visited often, and her recuperation, and the obvious efforts Mayhew was making, brought about a rapprochement between him and his son-in-law.

Returning to London in 1848 the mercurial Mayhew took a new direction. The Morning Chronicle launched a series on the condition of the working classes entitled Labour and the Poor Letters, which Mayhew possibly proposed. They appointed him their ‘Metropolitan Correspondent’ to expose the poverty of working Londoners. Once more Jerrold could take pride in this son-in-law. Sending a copy of the Letters to a friend, he crowed: ‘I am very proud to say that these papers of Labour and the Poor were projected by Henry Mayhew, who married my girl. For comprehensiveness of purpose and minuteness of detail they have never been approached. He will cut his name deep.’[xxi]

Within the year the Morning Chronicle fired him, though the reason was never clear. By now a national figure Mayhew continued where he had left (or been pushed) off by launching his own series, London Labour and the London Poor. In 1851 he dedicated the first volume to Jerrold ‘with whom knowing most intimately, the author has learnt to love and honour most profoundly’.[xxii] The warmth soon faded. In 1852, London Labour, a critical success but a financial flop, ceased publication in mid-sentence, sunk by an injunction over unpaid printers’ bills. Mayhew was on another downward spiral that led the next year to five months in the Queen’s Bench Prison for debt. Upon his release he took his family to the Prussian Rhineland, and four more years of exile.

By then Jerrold had left West Lodge to cut his costs, moving to St John’s Wood. His health continued to decline, and he died there in 1857. On his deathbed, he asked forgiveness from anyone he may have offended. Prompted about Henry Mayhew he whispered: ‘Yes, yes. God bless him.’ Dickens and Thackeray were pall bearers at his funeral. Though now forgotten, there is one legacy from his time on Putney Common that is very familiar. Writing for Punch from his beloved West Lodge, he coined the phrase ‘Crystal Palace’ to mock the Great Exhibition in 1851. The name stuck, so when the building was re-erected at Sydenham, his joke christened a whole swathe of south London.[xxiii] It was one born of the happiest time of his life, in his garden overlooking Putney Common, where, after a dinner-party under canvas below the great mulberry tree, there would emerge:

…the hearty host with his guests including Mr Charles Dickens, [where they] indulged in a most active game of leap frog … and foremost among the players and laughers was the little figure of Douglas Jerrold, his hair flowing wildly, and his face radiant with pleasure. [xxiv]

[source: Walter Jerrold Douglas Jerrold and Punch 1910]

[i] Mayhew, Athol, A Jorum of Punch (Downey, 1895), p. 20.

[ii] Slater, Michael, Douglas Jerrold: a life 1803-1857 (G. Duckworth, 2002), p. 139.

[iii] Jerrold, Blanchard, The Life and Remains of Douglas Jerrold (W. Kent, 1859), p. 306.

[iv] Jerrold, Blanchard, p. 180.

[v] Slater, p. 139.

[vi] Jerrold, Blanchard, p. 276.

[vii] Slater, p. 231-32.

[viii] Jerrold, Blanchard, p. 273.

[ix] Jerrold, Blanchard, p. 294.

[x] Hodgson, William Ballantyne, Life and Letters (D. Douglas, 1883), p. 58.

[xi] Slater, p. 232.

[xii] Slater, p. 233.

[xiii] Jerrold, Douglas, Mrs Caudle’s Curtain Lectures (Punch Office, 1846). Numerous editions are readily available via https://en.wikisource.org/ and https://archive.org/.

[xiv] Private MS quoted in Slater, p. 198.

[xv] Birmingham Gazette, 27 Oct. 1845.

[xvi] http://inflation.stephenmorley.org/.

[xvii] MSI 170/3/14 Morgan-Ray Collection.

[xviii] Horace Mayhew to Evans, Bodleian Library, Punch Archive, 2279-6.

[xix] Private MS quoted in Slater, p. 198.

[xx] Mayhew, Henry, German Life and Manners (W. H. Allen, 1864), vol. 1, Dedication.

[xxi] Cowden Clarke, Charles & Mary, Recollections of Writers (Samson Low, 1878), p. 290-91.

[xxii] Mayhew, Henry, London Labour and the London Poor (Office of London Labour, 1851), vol. 1, Preface.

[xxiii] Slater, p. 243.

[xxiv] Jerrold, Blanchard, p. 276