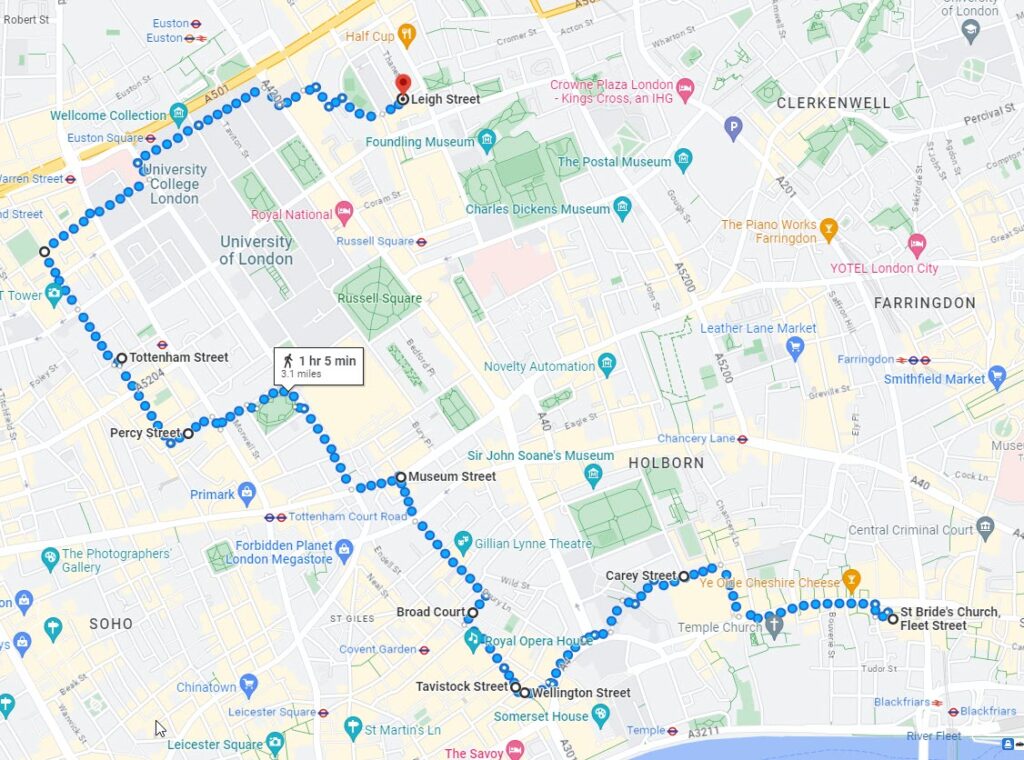

Join me on a stroll around Mayhew’s London for three or four hours on Sunday October 20th or Sunday November 17th.

Many places in London have associations with Henry Mayhew. The list here sets out a walk through some of the key ones. Non-stop, this walk takes just over an hour (according to Google).

Stop 1 | St Bride’s Avenue

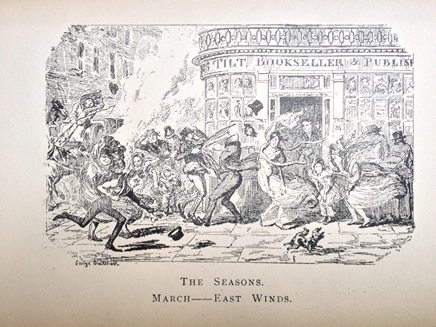

- David Bogue was Mayhew’s great supporter and publisher. His premises were at 86 Fleet Street, wrapping around the corner into St Bride’s Avenue. Bogue began work there in the 1830’s when Charles Tilt ran the firm. Tilt soon retired, handing the business onto Bogue, along with his authors and illustrators, including the renowned George Cruickshank

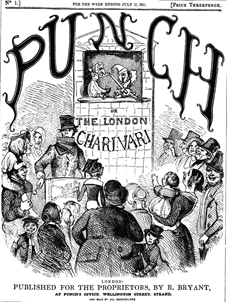

- At the east end of Fleet Street, to the north of Ludgate Circus, sat the Fleet Prison, London’s main debtor prison since the 12th century. Mayhew was incarcerated here from November to December 1833, along with his elder brother Thomas. In 1841, during the early, risky days of Punch, he bribed his way back in to work with another inmate, Henry Grattan, to produce the first Punch Comic Almanack, a Christmas special which saved the fledgling magazine from going under.

Stop 2 | Carey Street

- Mayhew’s father, Joshua, was a solicitor, who specialised in the bankruptcy courts. His law firm was located at No. 26 Carey Street. Mayhew was brought to work here after his return from India in 1828, a brief spell that ended disastrously.

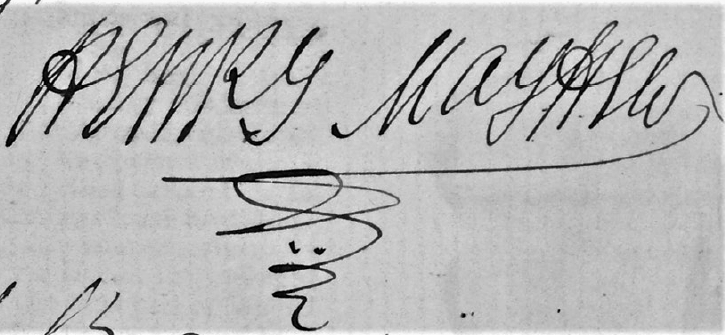

- In 1841, the founding deeds for Punch were drawn up there by Mayhew’s brother, Augustus (the only one of the Mayhew boys to follow in their father’s footsteps). Henry’s signature was the first among the five founders of the periodical that came to define Victorian culture.

Stop 3 | Wellington Street

- Wellington Street was the heart of Victorian periodical publishing. Dicken’s Household Worlds magazine was based here, as was G.W.Reynold’s more radical Reynolds Newspaper. In 1841, Punch’s first office was at No.3 Wellington Street.

- Mayhew returned here in 1851 when London Labour and the London Poor moved to offices at No.16 Upper Wellington Street.

Stop 4 | Tavistock Street

- Mayhew spent the last 30 years of his life moving from one rented room to another. His last was at No.8 Tavistock Street. Aged 74, he died here on 25th July 1887. He was buried at Kensal Green Cemetary.

- Mayhew’s last known public appearance had been seven years earlier at The Star & Garter, Leicester Square, to share his reminiscences about his early days with the crowd that formed Punch.

Stop 5 | Broad Court

- The Wrekin pub stood at 22 Broad Court and was where Mayhew and his bohemian coterie hung out in the 1830s. A portrait of them featured in The Town, a scurrilous journal for the London demi-monde.

- During the 1830s, Mayhew and his old Westminster school friend, Gilbert a’Beckett, published and wrote Figaro in London, a very successful satirical magazine and the forerunner of Punch, alongside many other more ephemeral productions like The Comic Magazine. Mayhew wrote under the pen name of Ralph Rigmarole, a ploy to evade police and debt collectors alike.

Stop 6 | Museum Street

- Mayhew lodged at 40a Museum Street in the late 1860s. In 1868 he spent time in the last remaining debtors prison in Whitecross Street. He applied to the Royal Literary Fund for relief, giving 40a Museum Street as his address. They gave him £50.

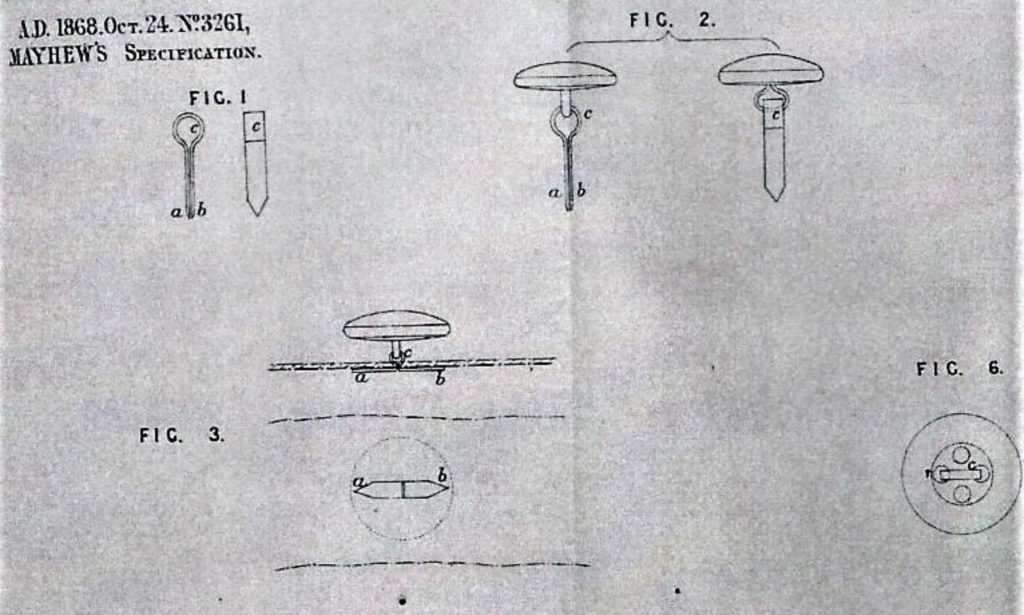

- In 1868, Mayhew also applied for a patent for a new invention – ‘An improved Button Fastening’ – designed to do away with needles and thread. Patent Number 3261 was approved by the Patents Office on 20 April 1869. One newspaper reported it under the headline ‘Single Men, May-Hew Evermore Be Happy!’

Stop 7 | Percy Street

- Mayhew and his family lived at No.15 in 1856, on their return from a couple of years in the Rhineland. Supported by his publisher Bogue, Mayhew planned to revive London Labour and the London Poor. He also worked on Bogue’s weekly paper The Illustrated Times, covering insurance frauds and the infamous Rugeley Poisoner trial at the Old Bailey.

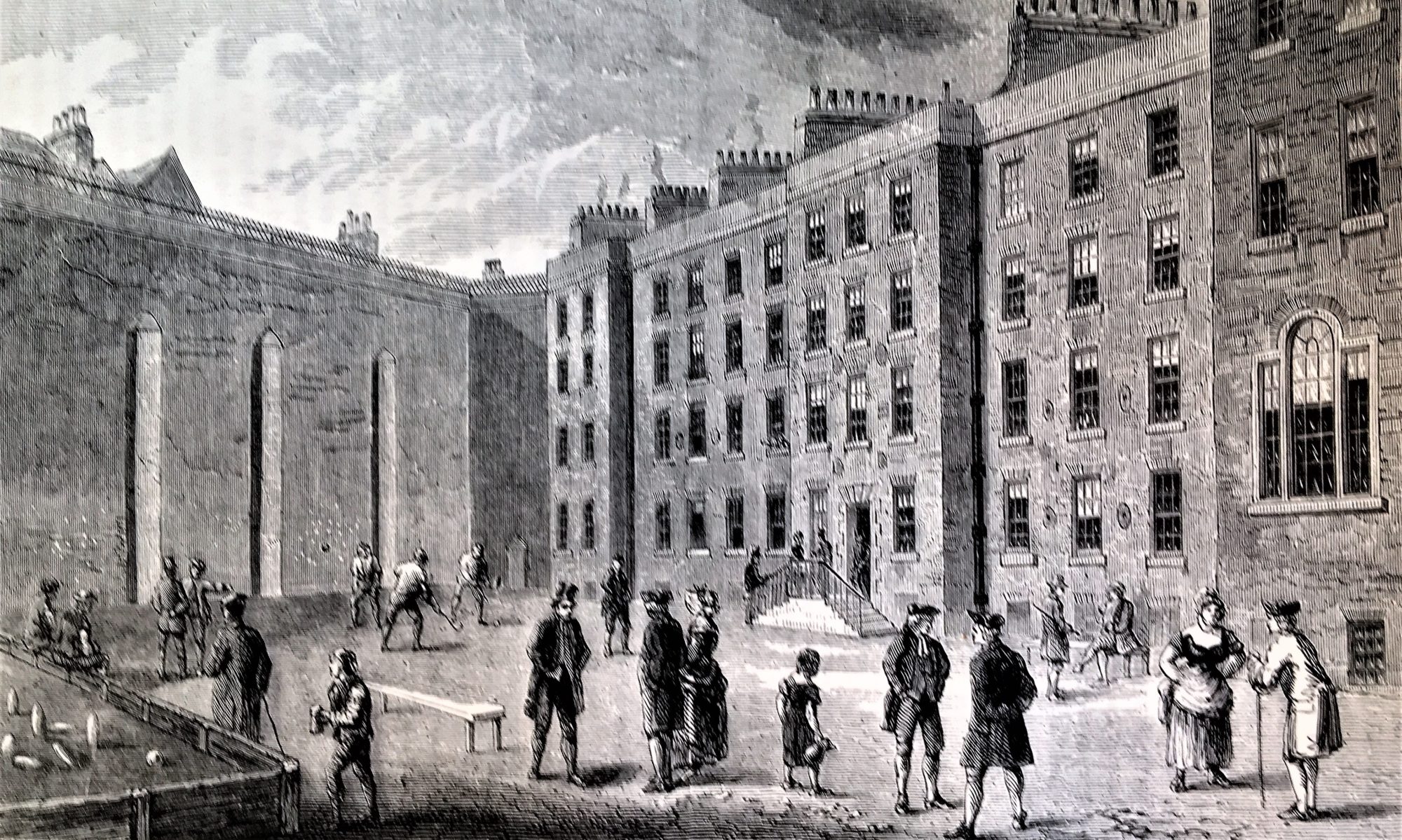

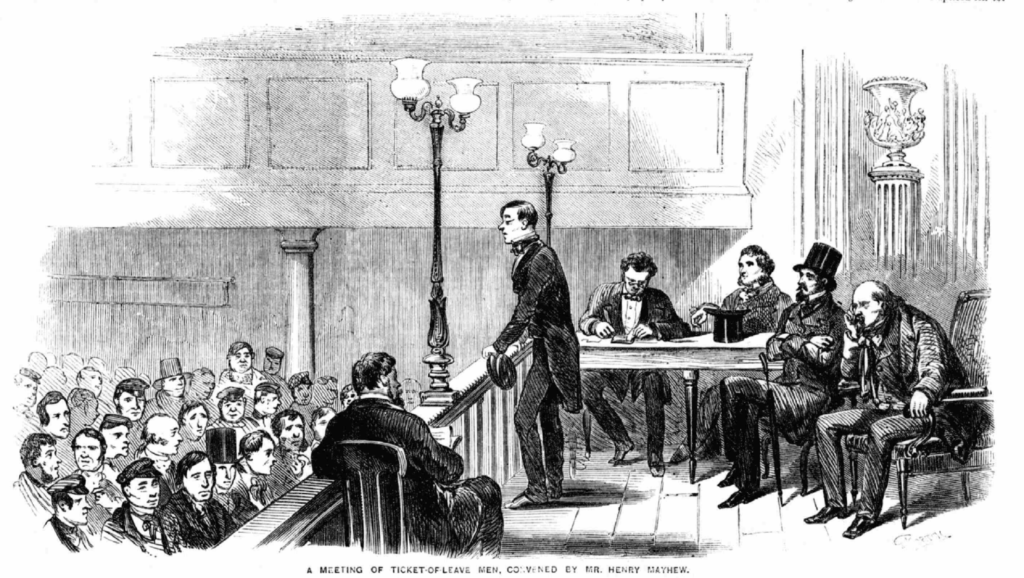

- In March 1856, Mayhew and Bogue launched a new series, The Great World of London. The plan was for Mayhew to cover the whole spectrum of life in London. He began with the criminal prisons, visiting each in turn, and developed a reputation as a pioneering criminologist. Bogue’s sudden death in November 1856 put an end to the series and all their other plans.

Stop 8 | Tottenham Street

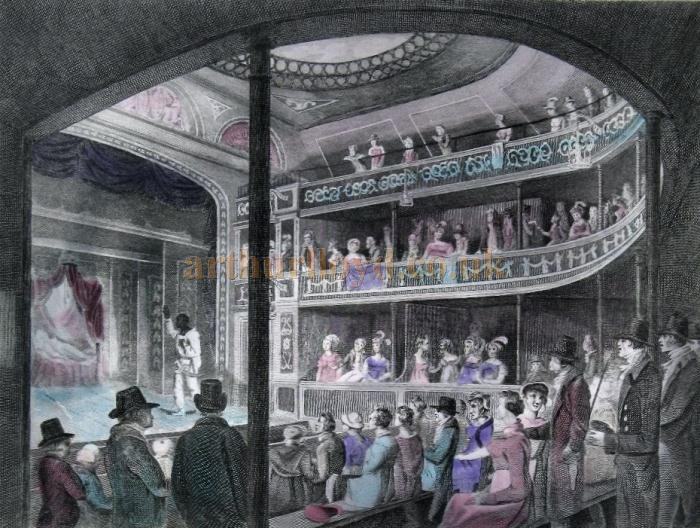

- Location of the Fitzroy Theatre, opened by Mayhew and Gilbert a’Beckett in 1834. They wrote and staged burlesque plays, including a musical, The Revolt of the Workhouse, which drew the censor’s eye. Mayhew’s main contribution was The Wandering Minstrel, which became a Victorian music hall favourite until the end of the century. Sadly, Mayhew sold the rights to it for £25, as the Fitzroy Theatre descended in disputes, court cases and debts. A’Beckett’s closing appearance was in the bankruptcy courts, while Mayhew disappeared to Paris to avoid the bailiffs.

Stop 9 | Fitzroy Square

- Mayhew was born in Great Marlborough Street (opposite where Liberty’s now stands). In 1827 his family moved to the more prestigious No.16 Fitzroy Square. That year Mayhew was expelled (or ran away according to his account) from Westminster school. In June, against his wishes, his father enlisted him as a trainee midshipman on an East India Company ship bound for Calcutta. On their return to London in 1828, Mayhew left the ship, returning home with just the shirt on his back and a tarantula in a jar.

- After his return from India, his father took the 16 year-old Mayhew under his wing at his law firm in Carey Street. Mayhew was bored there. One day, sent to lodge some urgent papers with the court, he instead wandered the streets, taking in the life there. That evening, court bailiffs turned up during dinner to arrest his father. Mayhew crept out the house, and stayed away for years.

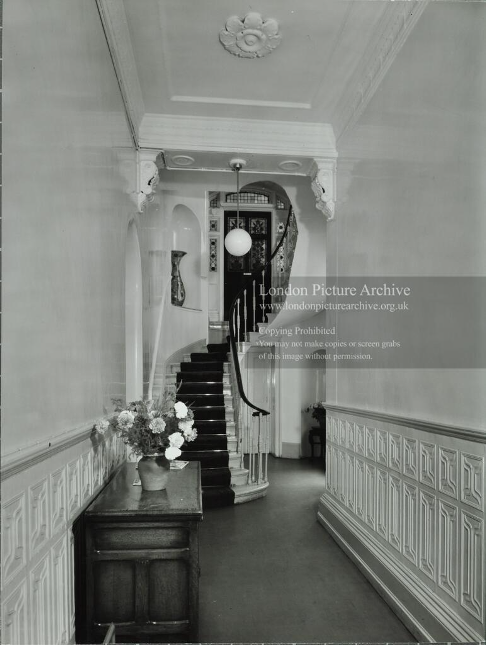

Stop 10 | Leigh Street

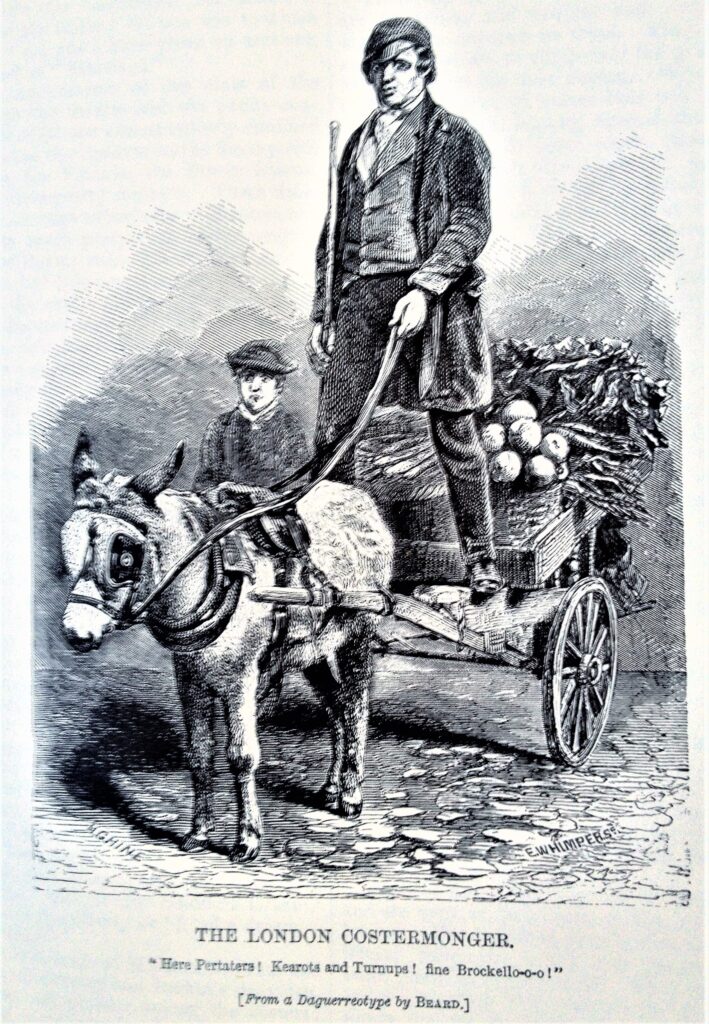

- In 1851, Mayhew lived at 1 Leigh Street while he worked on London Labour and the London Poor. His habit was to take the street people to Leigh Street for interviews, with his younger brother Augustus or another helper acting as stenographer. Critics said he plied them with drinks too, but that was a minority view.

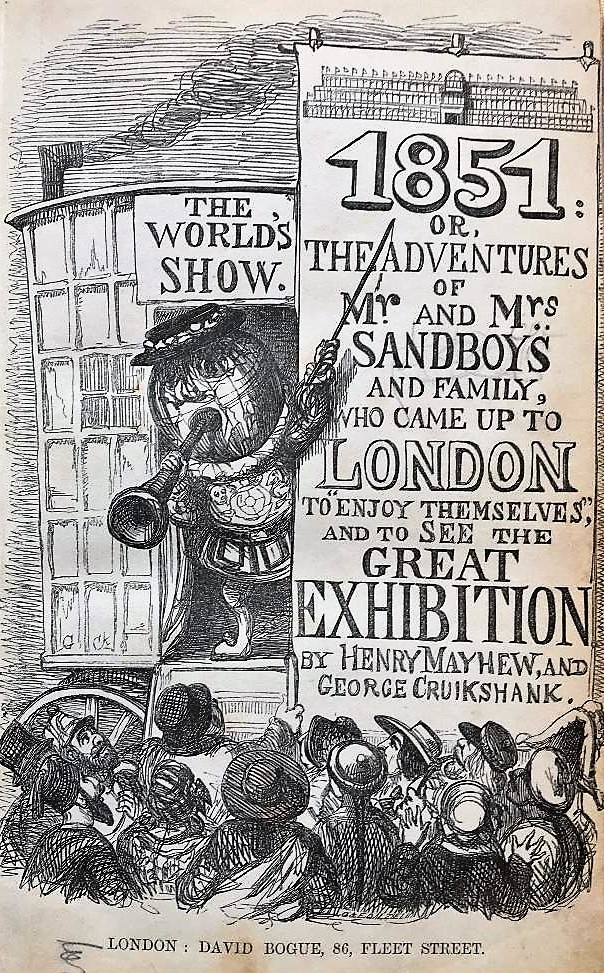

- With finances difficult (as ever) Mayhew worked on parallel publications throughout 1851. One, Low Wages, was an academic analysis of the causes of poverty. He argued poverty was endemic to unfettered capitalism, cementing his growing following among working class radicals and Tory protectionists alike. Another, more lighthearted, was 1851: or The Adventures of Mr and Mrs Sandboys and Family who came upto London to enjoy themselves and to see the Great Exhibition, a comic skit on the crowds flocking to London for the ‘Crystal Palace’ exhibition opening in Hyde Park. With his old friend George Cruickshank sharing the billing as illustrator, the monthly serial was said to be the fastest selling since Dickens’s Pickwick Papers.