The second edition of London Vagabond is available in paperback and on Kindle from Amazon. Here are the highlights of the new edition.

Mayhew & Ince, furniture makers

Mayhew’s grandfather was a partner in the firm of Mayhew & Ince, highly successful furniture makers and designers to the aristocracy in the late eighteenth century, who worked closely with Robert Adams. This is covered in The Making of Mayhew in the London Historian’s Newsletter, September 2023. Founded in Soho in 1762, the firm flourished for decades before dissolving in 1800 in debts, acrimony and a legal dispute over the assets that limped through Chancery until 1826. Mayhew’s father, Joshua, grew up in the shadow of the fallout, which may have influenced his choice of career as a bankruptcy lawyer and account for his pugnacious character.

The Satirist targets Joshua Mayhew

The Satirist, a dubious Regency paper with a reputation for blackmailing targets, dubbed Joshua Mayhew ‘the sharpest bankruptcy lawyer of his standing and station’, in one of their kinder moments.[i] They ran a column ‘The Black Sheep of the Law’ which featured him frequently in the 1830s. One case stood out. In 1828 Joshua Mayhew had acted for the Commission of Bankruptcy against a Bond Street banker, a Mr Chambers. Once the proceedings had left Chambers and his family destitute, Mayhew had him arrested and put in the Fleet prison for a mortgage claim he held against the banker. The mortgage deed empowered Mayhew to sell Mr Chambers premises, deducting his legal fees from the sale before giving the small remainder to Chambers. Instead, he sold part of the property, charged Chambers for the administration of the sale, and took over part of the property in Enfield Chase as his own country residence.[ii] The case then became mired in the courts, with Chambers held in the Fleet debtors prison for years, despite the potential value of the property Mayhew had control of being enough to settle his debts and free him. In one interim hearing, in 1835, an evasive Mayhew was cross-examined about his exorbitant legal fees by the Attorney-General. It turned out he had charged Chambers around £25,000 for his time on the case, all coming out of the estate of the prisoner he had flung in prison.[iii] The Satirist harried him throughout the 1830s, advertising for any further information on his conduct and calling for an enquiry

Mr Mayhew, the persevering attorney, has the reputation of being the sharpest bankrupt lawyer of his standing and station, and has the credit of having had the management of a considerable number of commissions, but this circumstance should rather stimulate an inquiry into Mr. Mayhew’s prodigious grasp of costs rather than stifle it.[iv]

[i] The Satirist, Sunday 23 July 1837

[ii] The Satirist, Sunday 21 June 1835

[iii] The Satirist, Sunday 01 November 1835

[iv] The Satirist, Sunday 23 July 1837

Ledru-Rollin and The Decline of England

Mayhew’s series of London Labour letters for the Morning Chronicle saw radical papers, like the Chartist Northern Star, The Red Republican and the Democratic Review, hail him as a true champion of the poor. The Christian Socialist Charles Kingsley, in Alton Locke, and Dickens, in Our Mutual Friend, borrowed liberally from his reports. They also caught the eye of Alexandre Auguste Ledru-Rollin, a leading French revolutionary who had sought sanctuary in London after the failure of the 1848 uprising. Contrary by nature, in May 1850 he published The Decline of England, a lengthy indictment of the place that had given him refuge, “that living picture of nameless griefs, called British Society”.[i] Here he praised The Morning Chronicle’s enquiry, and lifted large chunks of it to support his case for the appalling conditions and inevitable decline of England. Whole chapters were simple reprints of Mayhew’s Metropolitan Letters, on the dock labourers, coalwhippers, lightermen, Spitalfields weavers and more. A even-handed review in The Morning Chronicle noted how much of Ledru-Rollins 196 pages were “borrowed from our Letters on Labour” without resentment. Commenting on the preface, in which Ledru-Rollin made a ‘half-apology…for his apparent forgetfulness of English hospitality”, the review said none was necessary as

Our countrymen are supremely, almost culpably, indifferent to the opinion of foreigners; and we can conscientiously assure M. Ledru-Rollin, that an irresistible tendency to laughter will be the prevalent emotion in the minds of most English readers of his work.[ii]

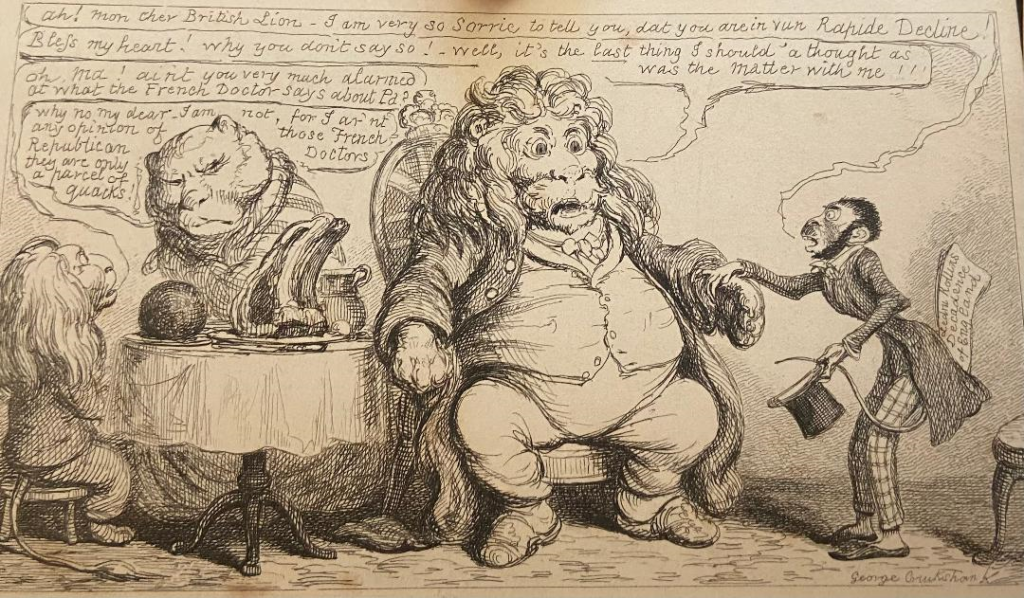

Mayhew proved the point. He had noticed the borrowing of his work. Editing the 1851 Comic Almanack he inserted spoof pages ‘A leaf out of Ledru-Rollins Book’ which began “My celebrated book (which I regret to say has already proved the ruin of my French publisher) I have left out many examples of the ‘Decline of England’ which I now hasten to supply”, these being the catastrophically low prices of anything from pineapples to haircuts to stilton cheese in England. No doubt at Mayhew’s suggestion, Cruikshank added a sketch in support: ‘The sick British Lion and the French Quack Monkey’. [iii]

The sick British Lion and the French Quack Monkey, George Cruikshank, Comic Almanack, 1851

Ledru-Rollin remained in London for the next 20 years, where he joined the executive of the Revolutionary Committee of Europe and, allegedly, plotted to assassinate Napolean III. An amnesty in 1870 saw his return to France and the National Assembly. He has since had an avenue and a metro station named after him.

[i] Ledru-Rollin, The Decline of England, 1850, p276

[ii] The Morning Chronicle, Wednesday 15 May, 1850

[iii] The Comic Almanack, 1851

Jane Mayhew reveals her hand

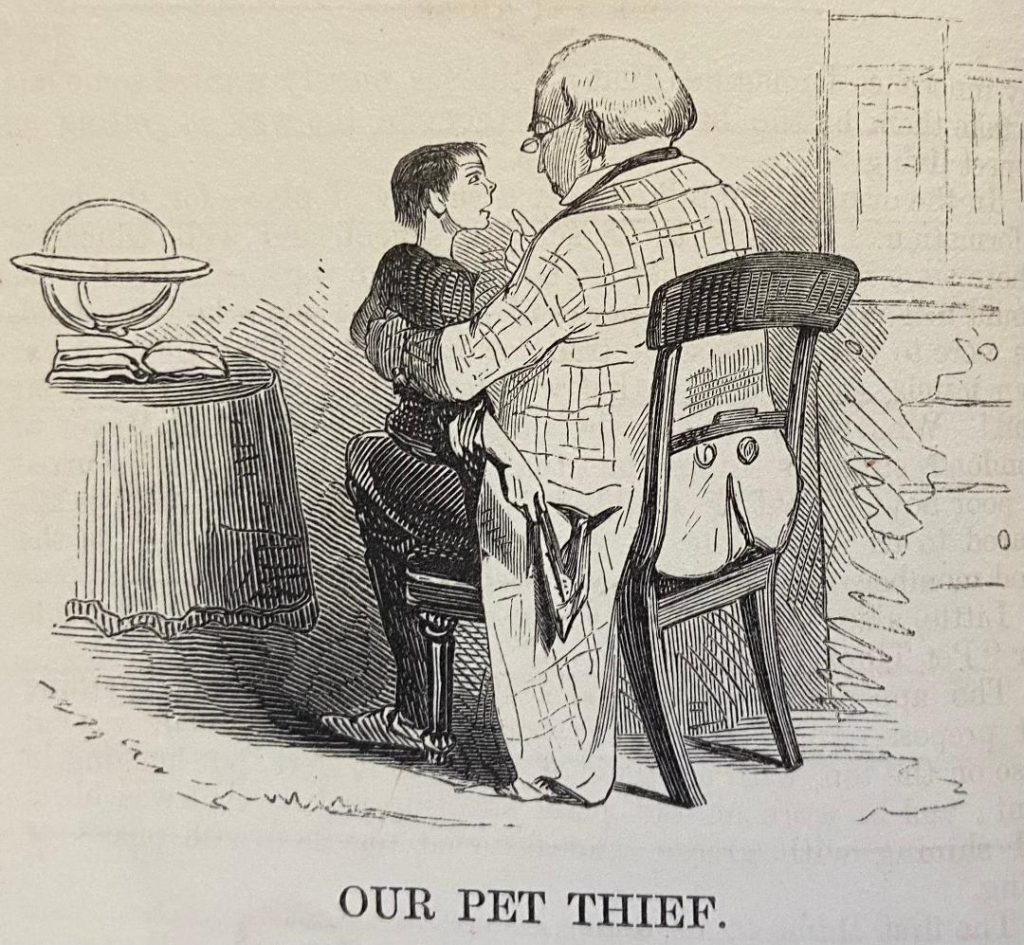

That years Comic Almanack also carried an article by Jane Mayhew ‘Our Pet Thief’. Mayhew had a habit of bringing his subjects back home. Following his meetings with street urchins he adopted a young pickpocket in an attempt to reform him. Mayhew is not named nor the author of the piece, but the provenance is clear

In making some enquiries relative to the state of the criminal population, my husband found it necessary to visit a low lodging-house, the abode of thieves and pickpockets. He there became acquainted with “Dan,” and (from his returning some money that was given him to change) took such a fancy to him, that he determined to try whether the lad… could not – if taken from his wretched and demoralizing associates – be induced to withstand all other temptations.”

They find “Dan” rooms above a coffee shop, and Jane recounts various attempts to reform “Dan”, his horror of a bath, giving headlice to the household, terrifying the cook with tales of his times in Newgate and his reasons for being there. His reputation also foils attempts to find a school or a position for him. Jane grows increasingly anxious about their guest, but Mayhew is sanguine.

My husband thought it would be a good “moral lesson” for our children to let them know that “Dan” had been a thief, and that he had been in prison a great many times; but that he had resolved to become a good boy, and that was our reason for having him with us. This, however, instead of having the effect intended, made the children look upon “Dan” as an object of great interest…

Mayhew attempting to reform ‘Our Pet Thief’ who lifts a handkerchief from his pocket, Comic Almanack, 1851

She finds her five year old Athol sitting on “Dan’s” knee listening to his tales open-mouthed. Jane questions him after and learns “our “pet pickpocket” had been telling the little fellow of the fun it was to go “sawney hunting,” which I afterwards learnt was stealing pieces of bacon from shop doors.”

The last straw for Jane comes when food starts to go missing from the house. Despite Mayhew’s defence that “Dan” was an easy target for the other servants to blame, he agrees to send him to America to start a new life and the “last we heard from him was that he and several “reformed criminals” from the London ragged schools were “working” (as the thieves call it) the city of New York.”

Written in a similar style to The Greatest Plague, published earlier that year, the article proves Mayhew’s later claim that Jane was a “sleeping partner” in the Brothers Mayhew. It ends on a warning from Jane, that would go unheeded

NB. The above has been written as a hint to certain philanthropic gentlemen, that the bosom of a quite family is not exactly the place in which to foster and reclaim a London pickpocket.[i]

[i] Comic Almanack, January 1851

The view from Eisenach

In 1861 Mayhew returned with his family to Germany, settling in Eisenach, Saxony, to research and write two books, one a children’s book, dramatizing the boyhood of Martin Luther, the other a two-volume analysis of German life and customs, which frequently descends in a diatribe. It is also a highly personal diary of his unhappy life in Germany. In the Preface to German Life and Manners he acknowledges his wife for the first time as the ‘‘sleeping partner’ of the firm’ of Mayhew.

The earliest photo of Eisenach, Saxony and Mayhew’s view from his writing window.

Source: Stadtarchiv Eisenach 40.2.03-25-712

In Eisenach, he assumed his favoured vantage point at a bay window, better to scrutinise the comings and goings on the KarlsPlatz, filling notebooks with derogatory observations on the locals and their culture. Athol photographed his view, looking west up Karlstrasse, the main street, the town square and gate being to the right. This photo, held in the Eisenach Archives, is the earliest photograph known of Eisenach. On the back is written “April 15 1862, KarlsStrasse, taken from our window, KarlPlatz, Eisenach.” The archivists had no idea who had taken the photograph or written the notes. Happily, a copy of London Vagabond is now with the Eisenach Archives, so a happy return, in a way, for Mayhew to the town he could not wait to leave.

London Characters

Mayhew’s writing is hard to trace in his later years when he worked as a ‘voluminous anonymous writer’.[i] He focused on journalism, a ‘leader writer, dramatic critic and magazine contributor’.[ii] I’ve tracked down a new source, London Society. Launched in 1862, with the byline ‘Light and Amusing Literature for hours of relaxation’.[iii] From April 1865 until December 1869 Mayhew was a periodic contributor of sketches, ‘word paintings’ as he called them, of London scenes and characters, from ‘Getting up a Pantomime’ to ‘Scenes in Court’.[iv] From September 1867 Mayhew wrote under the pseudonym of ‘the Thumbnail Sketcher’ with engravings by ‘Bab’ (W.S.Gilbert prior to Gilbert and Sullivan fame). Four sketches appeared from September to December 1867, ‘Thumbnail Sketches in London Streets’, in which, characteristically, Mayhew set off with his sense of fascination, picking out the apparently respectable passers-by in the street, he then unpeeled them to reveal they may not be what they seemed.

In 1870 the volume London Characters and the Humorous Side of London Life appeared.[v] No author was credited, not the source of the essays, but followers of ‘The Thumbnail Sketcher’ in London Society would have recognised both. London Characters pulled together all of Mayhew’s articles with no revisions. Even internal references to the previous weeks article in the original London Society remained. In April 1874 Chatto & Windus republished the work as London Characters; Illustrations of the Humour, Pathos and Peculiarities of London Life. Now Mayhew was named as the author and the illustrations credited to W.S.Gilbert (by then famous through his musical collaborations with Sullivan).

This version of London Characters added recycled material from Mayhew’s time as the Metropolitan Correspondent on the Morning Chronicle. The selection played up to the ‘Humour, Pathos and Peculiarities’ of the title. ‘ “Variant Vagabonds” or, London Characters without a character’ recycled his Letter III from October 26 1849 on the culture of the London docks casual labour, the last port of call for the outcast, where no questions were asked about the applicants. ‘Making Eyes’ recycled his interviews with dolls eye makers from 1850, while ‘The Curiosities of Drunkenness’ replayed the debate among coal-heavers on whether it was necessary to be drunk to do the work at all, first aired in 1849, which had resurfaced again in Griffin’s 1864 version of London Labour, as part of their padding out of his original work.[vi] A quarter of a century on, Mayhew was still collating and, in some places, revising the original London Labour material.

[i] Bury Times, Saturday 13 August 1864

[ii] Bury Times, Saturday 13 February 1864

[iii] British Library Crawford 847 Miscellaneous Stamp Pamphlets

[iv] London Characters and the Humorous Side of London Life, 1870, Stanley Rivers & Co [BL 10059.e.27]

[v] Bury Times, Saturday 13 August 1864

[vi] Morning Chroniclel, Letter XXI, December 28 1849

The last wish of Jane Mayhew

Jane Mayhew was living at 192 Cornwall Road, Notting Hill in 1880. Suffering from heart disease and bronchitis, she passed away on the 26th February, their son Athol by her side. When he registered her death, despite the 16-year estrangement, he gave her occupation as ‘Wife of Henry Mayhew – Author’. However amicable the separation, her final wish was to be buried alongside her father in West Norwood Cemetery, and not the Mayhew family vault in Kensal Green Cemetery (where Mayhew would be interred seven years later). In the first version of London Vagabond, I wrote she was buried under her maiden name, as a final rejection of her husband. This is not so. Her gravestone was swept away by Lambeth Council in a fit of absentmindedness in the Eighties, along with many others. Luckily, a record of her inscription was noted in Notes & Queries during a discussion on the centenary of Mayhew’s birth.[i] Her plaque, though retaining her married name, simply stated she was the daughter of Douglas Jerrold.

[i] Notes & Queries 11 S. V. Mar 30 1912