First published on the London Historians Members’ Newsletter September 2023. Many thanks to Mike Paterson for making this possible.

An enigma for much of his life, and ever since, one thing has been certain about Henry Mayhew, the legendary author of London Labour and the London Poor: he despised his father and the feeling was mutual. Joshua Mayhew was a lawyer who craved respectability, and his famous son lampooned him, and his calling, whenever he got the chance. A Respectable Man, published in his friend George Cruickshanks’ Comic Almanac in 1848, was a poem written with his younger brother Augustus, caricaturing their father as ‘Iscariot Ingot’, who uses the cloak of legality to extort a fortune as a moneylender, giving advances secured against their eventual inheritance to feckless young aristocrats, ‘Post Obit’ loans, listed in the “Blue Book”:

A highly respectable Man

Is Iscariot Ingots, Esquire,

He’s “Post Obits” on half of the “Blue Book,”

And a mortgage or two in each Shire,

And having more cash than he needs,

Why he lends to the poor all he can,

And only takes sixty per cent,

Like a highly respectable Man.

His house ‘like a nobleman’s furnished’ from treasures which ‘belonged to some peer of the state’, he beats his wife, then buys her gifts to assuage his guilt, bullies his children, who hide when they hear him coming home:

It is said he’s a tyrant at home,

That the jewels his wife has to show,

Were all of them salves for some wound –

That each diamond healed up a blow;

That his children on hearing his knock,

To the top of the house aways ran –

But with ten thousand pounds at his banker’s,

He’s of course a respectable Man. [i]

As a kind of revenge, all but one of his seven sons grew to spurn the ideals Joshua held. The journalist Sutherland Edwards, who knew all the Mayhew brothers well, said of them

To have known the Mayhew family was itself an education in the ways of Bohemian eccentricity. From Henry Mayhew, who wrote ‘London Labour and the London Poor’ and satirized his own father as ‘Iscariot Ingots Esquire’ in a comic annual, down to Julius Mayhew, who always cut his brother Horace’s hair and charged him sixpence each time, they were as amusing a band of clever incapables as were ever sent by Providence to plague a highly-respectable solicitor like Mayhew pere.[ii]

He also knew Henry and Augustus had no fear of their father being angered by A Respectable Man as ‘the sons were probably well aware that their father did not read their writings’.[iii] Even so he had their cards marked. When he died in 1858, a very wealthy man indeed, he appointed only his son-in-laws, all business men, as executors to his will which singled out Henry to receive a pittance, to be signed for in person weekly. Unlike all the other children, Joshua left him no personal possessions because: ‘To my son Henry I cannot make any personal bequest because he cannot possess any property to his own use’.[iv]

One source of his offspring’s grating bohemianism may have been Joshua own father. John Mayhew had been a leading furniture maker in the firm of Ince & Mayhew, a partnership set up in 1759, that thrived for the rest of the eighteenth century. To contemporaries, Ince & Mayhew stood with Chippendale for quality, reputation and the social cachet of their designs and craftmanship.[v] They worked for many aristocratic families, the Duke of Marlborough and the Prince of Wales among them. Robert Adams, the leading architect of the era, commissioned them on many of his projects.[vi]

John Mayhew and William Ince were born into the creative Soho milieu of craftsmen and artists. Ince’s father a glass-grinder and Mayhew’s a carpenter.[vii] Apprenticed to local cabinet makers, they became close friends. In 1762, they married the sisters Isabella and Ann Stephenson at a joint ceremony at St George’s, Hanover Square. The families were neighbours, in Marshall Street, Westminster, and set up their works there.[viii] Their business thrived, and the partnership expanded into property, buying up nearby sites, including two in Carnaby Street, and investing in rural locations like Crouch End and Hornsey. Social status followed and fed success. The pair became Directors of the Westminster Fire Office, members of the Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce and were inducted as masons too (albeit to different lodges).

Isabella Mayhew died in 1762, and John Mayhew remarried Bridget Winsley (Henry’s grandmother). Of their ten children, just five survived, among them Joshua, born in 1778. As he grew up, the business began to wane. By 1800 the firm was saddled with debt, from late paying clients and unwise property speculation. The partnership was dissolved amid personal acrimony. Disputes over realising the assets sparked legal actions that spanned decades. Ince died in 1804 and within weeks his widow Anne lodged a Bill of Complaint in the courts against John Mayhew to prevent him disposing of any partnership property. Mayhew counterclaimed, arguing he was due five times whatever Ince’s estate was, as he had put up most of the money for the partnership. Regardless of Anne Ince’s death in 1806, then John Mayhew’s in 1811, the case ground on through Chancery for years, only finally resolved in 1826. Joshua Mayhew had qualified as a lawyer by 1802, his legal career forged within this bitter financial and personal fallout. By and large, Ince had been the creative driver of the partnership, while Mayhew had led the commercial side, though not exclusively. [ix] This may have shaped Joshua’s view on what mattered in life. Then there was his dying father’s fury with his elder brother, John, who had been raised to take over the family business but who had been declared bankrupt. In his will, John Mayhew lamented he was waiting for God to relieve him ‘from this troublesome life’, singling out his eldest son John “whose imprudence was the origin of my sorrows.”[x].

As a lawyer, Joshua Mayhew specialised in debt and insolvency, featuring often in bankruptcy court reports of the London Gazette and The Times. He started out in Symonds Inn, a dingy courtyard off Chancery Lane, featured in Dickens’ Bleak House as a failing legal ghetto. His practice flourished and he moved to 26 Carey Street, between Lincoln’s Inn and the Strand, the area then a warren of medieval alleys and streets, conveniently close to the bankruptcy courts. He prospered, acquiring properties across London, a portfolio of houses, shops and pubs in Piccadilly, Russell Square, Fleet Street, and Clerkenwell, and, south of the river, industrial sites in Rotherhithe and Bermondsey.[xi]

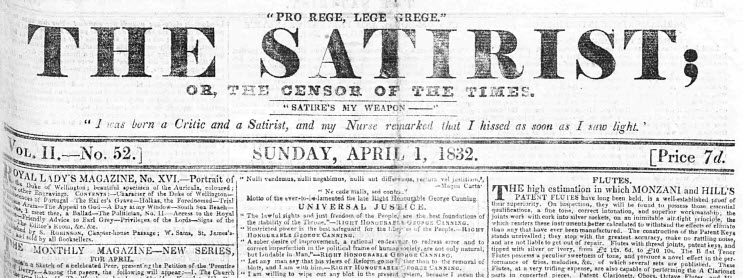

But the way he amassed his wealth drew opprobrium. One of the livelier Regency newspapers, The Satirist, with a reputation for blackmailing targets, called him ‘the sharpest bankrupt lawyer of his standing and station’, in one of their kinder moments.[xii] They ran a regular column ‘The Black Sheep of the Law’ which featured Joshua frequently in the 1830s. One particular case stood out. In 1828 he had acted for the Commission of Bankruptcy against a Mr Chambers, a Bond Street banker. The proceedings left Chambers and his family destitute, at which point Mayhew had him arrested and imprisoned in the Fleet for a mortgage claim he had against the banker on his country retreat in Enfield Chase. The mortgage deed empowered Mayhew to sell the premises, take the money owed him, then hand Chambers the remainder. Instead, he sold part of the property, charged Chambers for the administration of the sale, and took over part of the property as his own country residence.[xiii] As The Satirist reported in detail, the case then bogged down in the courts. Chambers remained in the Fleet for 12 years, despite the potential value of the property controlled by Mayhew being enough to settle his debts and free him. At an interim hearing in 1835 an evasive Mayhew was cross-examined over his exorbitant costs by the Attorney-General. It turned out he had charged Chambers around £25,000 for his time on the case, all coming out of the estate of the prisoner he had had flung in the Fleet.[xiv]

The Satirist harried him throughout the 1830s, advertising for any further information on his conduct and calling for an enquiry:

Mr Mayhew, the persevering attorney, has the reputation of being the sharpest bankrupt lawyer of his standing and station, and has the credit of having had the management of a considerable number of commissions, but this circumstance should rather stimulate an inquiry into Mr. Mayhew’s prodigious grasp of costs rather than stifle it.[xv]

Chambers was finally freed in 1838, a broken pauper. That year, The Satirist sent up the Lawyers Clerks annual dinner, with Joshua Mayhew “of Chambers notoriety” as the guest of honour at the venal feast, “called on to sing in honour of his profession”:[xvi]

The Law ! the Law the ! the roguish Law !

Which honest men e’er shun with awe;

Without a check, without a bound,

It sendeth its writs the nation round;

It plays with the fool, it mocks the wise,

And, like Old Nick, ‘tis crammed with lies

I’m in the Law ! I’m in the Law !

I’m the man for querk or flaw,

With the courts above and the courts below,

And costs abound where’er I go.

If a verdict comes and my clients fail,

What matter? They must go to gaol.

So, Henry Mayhew was not the first to attack his father in verse. In his own work, the conflicting pulls of respectability and bohemianism sharpened his eye for, and disdain of, cant. He would have been aware too, of this grandfather’s creative success and the fall of the partnership of Ince & Mayhew. He never referred to it specifically, yet perhaps his focus in London Labour on the cabinet making trade, the growing conflict between the quality craftsmen of the West End and the slop traders of the East End, with the way one took the ground away from the other, was an echo of that family breach.

[i] The Comic Almanack, 1848, pp.204-5

[ii] The Times, 1900, Review of Sutherland Edwards Personal Recollections.

[iii] Sutherland Edwards, ‘Personal Recollections’ p.57. 1900

[iv] Joshua Mayhew, Will, 9 March 1858, p.3-4

[v] Sarah Ingle, William Ince – Cabinet Maker, 2020, p.61

[vi] Hugh Roberts and Charles Cator, Industry & Ingenuity. The Partnership of William Ince and John Mayhew, 2022, p.27

[vii] Ibid, p.10

[viii] Sarah Ingle, William Ince – Cabinet Maker, 2020, p.49

[ix] Hugh Roberts and Charles Cator, Industry & Ingenuity. The Partnership of William Ince and John Mayhew, 2022, p.13

[x] Sarah Ingle, William Ince – Cabinet Maker, 2020, p.121

[xi] The Times, Saturday 10 April 1852

[xii] The Satirist, Sunday 23 July 1837

[xiii] The Satirist, Sunday 21 June 1835

[xiv] The Satirist, Sunday 01 November 1835

[xv] The Satirist, Sunday 23 July 1837

[xvi] The Satirist, Sunday 18 February 1838